|

Photo courtesy Mary Jane Piotrowski |

Lost River Ranch Letter

In the days long before the Internet and satellite TV, receiving the weekly farm paper in the mailbox was a big deal. For many families on the Prairies in the late 1960s, the first place they turned to in the Free Press Weekly was the Lost River Ranch Letter, a column written by southern Alberta rancher, George Ross.

Some called him the “Will Rogers of Canada” for his down-to-earth perspective, humorous stories and no-nonsense views on cattle industry issues. His colourful descriptions of the realities of life on the wide open plains, and the characters that he rubbed shoulders with, captured the imaginations of readers across the country.

Ross was a rancher, an industry spokesman and a pilot, but daughter Mary Jane Piotrowski says he really was a journalist at heart.

“Dad loved his cattle, but his second love was writing,” she recalled. “He pecked away at his typewriter with two fingers.”

It was a hobby he worked at diligently, and he loved ending each column with a joke and the expression “Oh boy!”, although his family recalls that not all of his jokes made it past the editor’s desk.

George Ross was from a legendary ranch family. He was the son of George Ross Sr., and grandson of Walter Ross, who had established Ross Ranches on a 24-section government lease on the Milk River Ridge in 1900. By 1912, Walter Ross and his partner of the day Jim Wallace would ship between 2,000 and 2,500 steers to the Chicago market. As their sons became involved, Ross Ranches controlled vast blocks of rangeland in both Saskatchewan and Alberta.

|

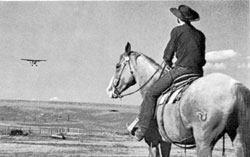

All three Ross brothers had inherited a love of flying, and with their spread so far reaching, they pioneered the use of small planes as a management tool. The Rosses were all instrumental in the Flying Farmer organization. It was George’s brother, Stubb Ross, who founded Time Air, which eventually became part of Canadian Airlines.Photo courtesy Mary Jane Piotrowski |

George Ross Sr. was a pilot with the Royal Air Force in Britain, where he met and married his Scottish wife Rodney, and they settled on the holdings of the Milk River Ranch. There were four children, Grace, George Jr., John (Jack), and Walter (Stubb). In 1949, George Sr. and his sons joined with oilmen Neil McQueen and Art Mewburn to purchase 160,000 acres and set up Lost River Ranches Limited, with George Ross Jr. as the president of the company, headquartered at Manyberries.

As the oldest son, George’s destiny was clear. He studied at Olds Agricultural School and in Port Hope, Ontario. Like his father, he joined the Air Force but was grounded due to spinal meningitis. While stationed in Summerside, P.E.I., he met his future wife, Eileen Barton. George’s charm and his stories of the adventurous West proved irresistible. They married and moved to the Lost River Ranch. It wasn’t always, or perhaps ever, easy dealing with unpredictable cattle markets, harsh weather, loneliness, and a strong mother-in-law, but Eileen adapted and became an integral part of ranch life raising their two children, Mary Jane and George Graham Ross III.

George became active in speaking up for rancher’s rights through the Western Stockgrowers Association. Like George Sr., he served as the group’s president, from 1961–?64. He was also one of the organizers of the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association, and served as its first manager. As well, he was a member of the senate of the University of Lethbridge, and chaired a federal advisory committee on animal research. With scientists at both the Lethbridge and Manyberries Research stations, he worked on developing a new crossbred type of cattle that could excel in the rugged range conditions. He was in demand on the speaking circuit and made friends, and undoubtedly ruffled some feathers, as he talked about cattle politics at livestock events across Canada. He spoke with authority as his outfit included some 6,000 head of cattle on 273,000 acres?—?the largest ranch in Alberta at the time.

Lost River Ranch Letter QuotesOn hobby ranchersEach year, more and more land is being taken over by these armchair cowboys and they don’t seem to care how much they have to pay for it or what the taxes are… These new ranchers are using cows for a different purpose now. Our idea was to manufacture beef out of grass and sell it at a profit. These fellows now don’t care whether there’s any profit in the cows or not. They don’t need it. —?March, 1968 On government in generalThe trouble I think is that we need more cowboys in Ottawa and more Ottawa representatives in the West. —?February, 1969 |

It was during one of his speaking appearances in Manitoba that George was approached by the Free Press Weekly editor Bruce McDonald to “write the odd thing for his paper.” George agreed, and his first column appeared under the heading: “Always welcome?—?a stranger?—?a friend?—?a chinook in winter?—?a rain or calf in summer.” His column quickly gained a following across the country. His fan mail was enormous and he rapidly became a celebrity both in cattle circles and the urban population.

Ross had tremendous insight, and ranch issues he addressed in his columns more than forty years ago are just as relevant today. He loved to relate stories of the range and the early days, but he also addressed topics ranging from hobby ranchers to bilingualism.

Sadly, George Ross’ creativity and ranching efforts were cut short when he died after a heart attack in 1971 at the age of 48.

Those letters are a treasure, giving George Ross a voice to this day, on life as he saw it, from the Lost River Ranch.