Tips & Tricks from a Wilderness Wrangler

The sight of a cozy camp of wall tents with stove pipes smoking high in an alpine meadow, a couple of days from the nearest road, is the reward wilderness wranglers enjoy and take pride in.

|

|

There can be no greater gift in life than the ability to experience the wilderness on horseback.

One’s survival and comfort depends on a good working knowledge of appropriate equipment and the ability to use the environment skillfully. Horseback in the back country vastly increases the pleasure to be enjoyed in these remote, pristine areas but only in the presence of adequate knowledge and skill. Nature in the raw can be an unforgiving place where trauma, hypothermia, and disorientation await.

Knowledge and experience means the difference between a winner and a wreck.

There are five important keys to survival in the wilderness, but often the most important receive little or no consideration. Listed in order of priority they are:

A Plan

A well thought-out plan is Number One because it can turn a panic situation into the ability to make the best of any circumstance. A failure to plan is a plan for failure.

Another important consideration for your plan is First Aid. You should be prepared in the event that a horse or rider is injured, and realize that you could be in a remote area far from medical help. Leave your name, planned route, destination, and expected time of return with a person familiar with the nature of the trip. Allow for a reasonable grace period, and agree on a plan of action in the event the party is overdue.

Shelter

Shelter can be a wood stove in a wall tent or just good quality rain gear?—?depending on whether the trip is days or hours in length.

Warmth

Warmth includes adequate layered clothing but also the ability to build a campfire in the rain. Remember: There is no bad weather, just bad clothing.

Photo courtesy BJ Smith

Water

Experienced mountain wranglers keep track of the watershed they are in, and use the creeks and rivers for navigation as much as possible. A keen eye for changing weather patterns, cloud formations, high-altitude wind indications, and the behaviour of wildlife can be helpful in predicting what is to come.

Food

Once the number of riders and length of the trip is determined, prepare a menu from the time of departure ’till the time of return. The right amounts of food, preferences, and allergies can then be taken into account. The most perishable should be eaten first. Make sure to include saddlebag trail snacks such as energy bars, trail mix, and bottled water. Leave personal hygiene items to the individual, but don’t forget camp cleaning supplies such as biodegradable soap, towels, and a dish pan for overnight trips.

Photo courtesy BJ Smith

Horses

Strong, sound, sensible, solid-boned mounts familiar with steep terrain, water crossings, and muskeg should be considered. A good knowledge of hobbles is welcome. The confidence of the rider helps the horse to be courageous and provide a safe ride in very challenging conditions. Understanding equine psychology is best for you and for them. In order to get the most from your horse, you need his trust and his respect.

Tack

Be sure your tack fits your horse. A double, three-quarter rigged stock saddle with a horn, six to eight tie strings, and a breast collar is very suitable for trail work. The back cinch should be kept snug. When double padding, the bottom pad should be an inch ahead of the top pad, which should be an inch ahead of the skirt to avoid backward slippage. If the pad is going to move, it will go out the back end.

Wilderness trails are best travelled at a reasonably slow, consistent walk. This is particularly true if there are several riders or pack horses in the group. Four miles per hour is considered normal and will result in far less trouble. Inclines should not be taken at a jog or lope, even though horses have a tendency to attack slopes. Many a good cowboy has lost his life off a loping horse on a steep slope.

|

|

|

|

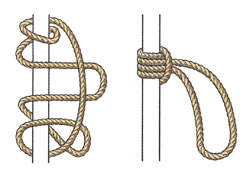

High Lines

It isn’t always possible or preferable to let your horses graze freely, even if they are hobbled. Picketing your horses on a high line is a good alternative and much better than tying to trailers or trees. The holes pawed by frustrated horses are visible for many years.

The high line should be high enough for your horse to walk back and forth under it. They like to shift directions to get a good view of everything around them, and if they are not restricted from turning back and forth, they will be much less frustrated and not prone to paw the ground or become distressed.

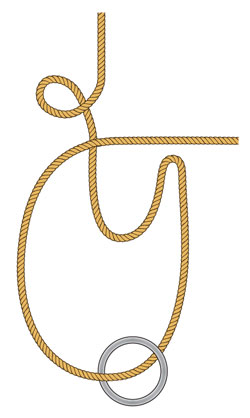

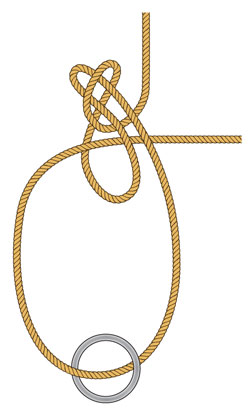

Don’t put horses on the line with their tack on. Fifty feet of static, non-stretch, half-inch line can hold several horses for several nights without lasting marks on the environment. Tying lead shanks to a separate lighter cord or twine between the picket line and shank will allow a chronic pullback to break away without taking the whole bunch with him. A Dutchman knot or ratchet strap is handy for tightening the picket line, and a Prusik hitch works great for attaching a breakaway cord to the line.

|

|

| This super simple Dutchman knot is an excellent tightening knot to tie down loads or to increase tension on a high line. To illustrate this knot, imagine the “standing” end of the rope at the top of the photo is already tied to one tree; the brass ring at the bottom of the photo with the “running” end of the rope passing through it signifies the other tree. Form the knot and pull on the “running” end of the rope to tighten your high line. Secure the running end with a couple of half hitches. Sisal is recommended to use for a high line, as there is no stretch in it. Pad the trees under your high line to protect the bark. Dutchman Knot made by Don Wudel and drawn by Zuzana Benesova |

|

Environment

Take pride in your outfit and your camp. Always clean up or spread manure left at a picket line. Remember: If you can pack it in full, you can pack it out empty!

For more info visit www.bjsmith.ca or www.oldscollege.ca.

B.J. Smith is an Equine Canada & Certified Horse Association riding coach, an experienced horse trainer, packer, clinician, award-winning cowboy poet, survival expert, and Canadian Ski Patroller. His course, The Wilderness Wrangler, is offered by Olds College.