Dr. Ryan Brook has been trying to incite a war against Saskatchewan’s wild boar for several years, and it appears as though his efforts may now be paying off. A University of Saskatchewan assistant professor, Brook has been studying the wild boar population in the province since 2011. At first, all he wanted to do was confirm what had been largely anecdotal accounts. “We started setting up trail cameras in a few places around Saskatchewan, and we started to see a lot,” he said.

But proving the wild boar were present in the province was just the beginning of Brook’s battle because then people began doubting whether the wild boar could reproduce in the wild.

Wild boar are native to Eurasia and North Africa, but they are not native to North America. Their introduction for sport hunting has created a management crisis in the United States, costing the country’s agricultural industry more than $1.5 billion USD annually. The current U.S. population of wild boar is estimated at four million, and they are spreading northward at a rate of up to 12 kilometres every year.

Brook, who specializes in wildlife ecology and wildlife-livestock interface, warns that Canada could end up in the same boat if swift action isn’t taken.

“These wild boar are incredibly well-adapted to cold,” he warned. “Some people assume they would never survive a Saskatchewan winter. That’s a bit naïve, given where they survive in Siberia.” Brook used remote wildlife cameras and was able to prove that the wild boar wasn’t just surviving in Saskatchewan — they were thriving.

“We actually captured images showing females walking by the cameras in the wild with multiple litters, showing they were clearly reproducing,” he said. Despite that revelation, Brooks says the issue failed to gain much traction with the Saskatchewan government, until recently.

An Unexpected Ally

Brook’s research stalled from the lack of funding and interest from Saskatchewan and the rest of Canada. That’s when Uncle Sam stepped in.

“We developed a relationship four years ago with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and we went into phase two of our research, which was much more expansive,” Brook said. “There’s a very real concern of wild boar going into the United States from Canada,” Brook said.

A Wild Problem with Captive Roots

Canada’s wild boar problem arose from an initiative in the 1980s and 90s to diversify agriculture. Exotic species fenced and farmed included reindeer (caribou), moose, elk, white-tailed deer and imported wild boar. Producers were encouraged to crossbreed domestic pigs with wild boar to increase litter size and frequency of the new imports. Brook says the resulting hybrids have much higher reproductive rates. “Those reproductive rates are really at the heart of the issue here, and the single biggest reason why it’s going to be such a challenge to try and manage this.”

Hunting “Farms”

Wild boar are also raised for the penned hunting industry in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Quebec. The concept is common in Texas, where people can hunt giraffes and kangaroos, but it should be no surprise that the state has a huge problem with exotic species, such as warthogs and aoudad that have escaped fences and set up shop in sensitive eco-systems.

The issue is controversial in Canada, with many hunters and non-hunters alike believing penned hunts are unethical. Regardless of where one stands on the issue, one thing is certain — escapes happen from these types of operations too.

Good Fences Make Responsible Neighbours

As unbelievable as it sounds, a large part of the problem has been the intentional release of wild boar.

“We’ve had massive numbers of escapes and quite a number of operations that have allegedly just cut the fence and let the wild boar go. So when we see those huge releases of 100-300 animals in one shot, they end up in the wild and they’ve done very well.”

Many releases aren’t intentional. Fences are not foolproof, and animals consistently surprise people with their persistence and ingenuity. Fences and outdoor livestock also allow for interaction between wild and domestic animals. Brook has observed domestic pigs and wild boar on the same side of a fence, and sometimes they’re making more than small talk.

“There’s one operation in the southeast where every single piglet that was born that spring had cream-coloured horizontal stripes that were very clearly sired by a wild boar.”

Ecosystems and Landscapes

While wild boar can certainly cause tremendous damage to the agricultural industry, the effect on native wildlife, ecosystems and sensitive landscapes is potentially devastating. Saskatchewan is home to an array of unique areas, including much of what remains of Canada’s native grasslands.

As versatile, opportunistic omnivores, wild boar are not limited by one food type or habitat, and groups (called sounders) of as many as 14 individuals have been documented. “They’ll eat literally just about anything, and they will kill and eat white-tailed deer. We have trillions of calories spread across the landscape,” Brook said.

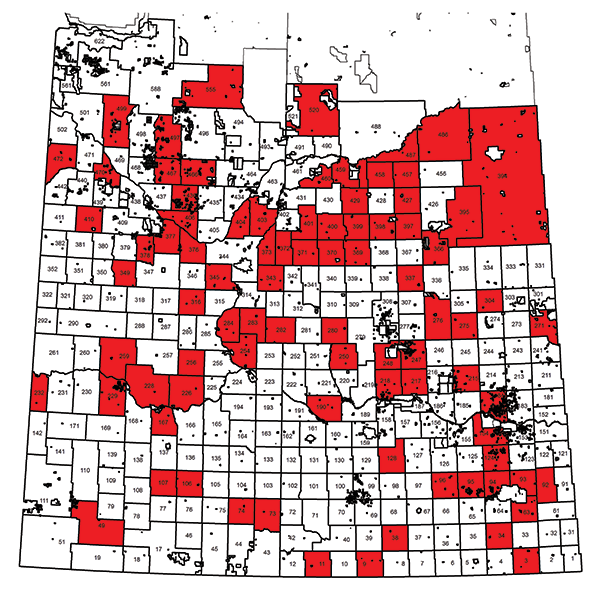

Saskatchewan may be the province with the biggest problem, but it’s not the only province with a pig problem. “All provinces except the Maritimes currently have at least some wild pigs,” said Brook.

In response to the wild boar problem, the Saskatchewan government changed regulations to allow residents to hunt them all year. However, research consistently shows that sport hunting pressure actually makes the problem worse because it scatters the animals and makes them more wary of human activity.

Brook says the only method to eradicate the boar is to remove entire sounders at a time. He says every province has been dealing with the issue differently, but that they all have a plan — all except Saskatchewan.

Darby Warner, executive director of insurance for the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation (SCIC) says they’re working on it. “In our history, there’s been about 50 claims for damage to crops from wild boar. In all of those claims, there’s been another wildlife animal included in that, so it’s really hard to tell how much damage is caused by the boar because boar is just one of the contributing factors,” he said.

The SCIS responds to wild boar sightings and attempts to remove the animals from the landscape once reported. Warner says the program has been quite successful, and he doubts whether the wild boar are as prolific as Brook’s research demonstrates. “They don’t seem to be as successful as Dr. Brook is trying to portray,” Warner commented.

Saskatchewan doesn’t have a management plan yet, but they’re working with Alberta to develop one. “We just want people to be aware that there are wild boar on our landscape, living in a feral state, and the problems that it brings,” said Perry Abramenko of Alberta Agriculture and Forestry. ‘But given the risks and the damage to the landscape, the risk of disease, the damage to crops, the damage to stored feeds… we don’t want them on our landscapes.”

Lorne Scott, Nature Saskatchewan’s conservation director and Saskatchewan’s environment minister from 1995 until 1999, says the government must take decisive action. “Today there are 20 or so wild boar farms remaining in the province, and despite the fact that the wild boar are documented in well over 100 municipalities, the province is still reluctant to terminate the industry,” said Scott, who is also a farmer.

He says Nature Saskatchewan has passed a resolution asking for an end to the wild boar farming through government buyouts of wild boar farmers at fair market value. The organization has also passed a resolution calling for meaningful funds for eradication efforts. Scott says Saskatchewan has delayed for too long and isn’t doing nearly enough to address the issue. “Other jurisdictions realize the significance of this problem and Saskatchewan is just sitting with a blind eye and refusing to intervene in any way, shape or form,” he said.

Brook is hoping the Saskatchewan government is starting to take the wild boar problem more seriously. “There really isn’t anything in Saskatchewan that you would call bad habitat for wild pigs. The window to deal with this is closing very rapidly. Certainly, within my lifetime, we could have more wild pigs than people in Saskatchewan,” Brook said