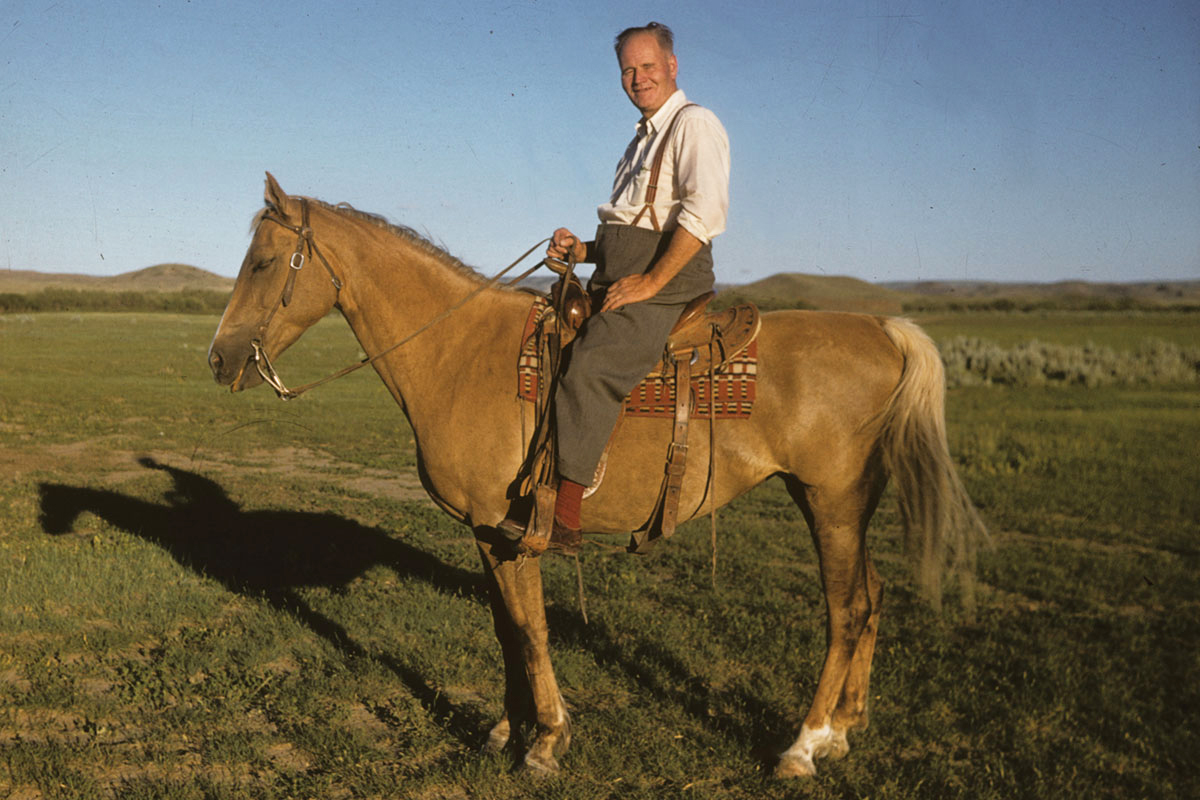

William Everett Baker came to Canada in 1917 as a door-to-door salesman. He was born in Minnesota in 1893. After graduating from university, he took a passenger train to Saskatchewan, stopping periodically to peddle the People’s Home Library. He was so successful that he was able to buy a half-section farm near Aneroid.

In 1918 he married his childhood sweetheart, Ruth Hellebo, and the couple settled down to farm and raise a family. The farm limped along until 1924, when Baker became manager of the Aneroid Co-operative Association. The co-op was successful, and in 1937 his reward was a position as fieldman for the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool.

Baker was always intrigued by history. While criss-crossing the province, he realized that a lot of heritage was being ploughed under as more and more grassland became farmland.

He was nearing retirement from his professional life when he was named president of the new Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society. The Society’s first project was to mark the fast-fading trail between the Cypress Hills and the Wood Mountain Uplands. Parts of it were already gone, and he could envision more disappearing. In his words, “The Trail between the Cypress Hills and the Wood Mountain Uplands was, at one time, as significant as today’s Number 11 Highway between Saskatoon and Regina.”

First Nations people had travelled east-west between the Cypress Hills and Wood Mountain Uplands forever. By the 1860s and ’70s, the route developed distinct characteristics as Red River carts filled with buffalo hides belonging to Métis traders left a rutted trail across the sea of grass. In the mid- 1870s, the Trail became associated with the North West Mounted Police (NWMP), who used it to travel between their posts at Fort Walsh and Wood Mountain. An estimated 5,000 Lakota and Dakota Sioux, including Lakota Chief Thathá?ka Íyothake (Sitting Bull), had sought refuge at Wood Mountain after annihilating Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of Little Bighorn. James Walsh, commander of the NWMP at Fort Walsh, was in charge of ‘keeping the lid on the pot’ and travelled that trail countless times while he and Sitting Bull developed a relationship of mutual respect.

The Mounties phased out their mounted patrols in 1912, but the Trail was not forgotten; older people still spoke of it. So, in the late 1950s, when the Saskatchewan History & Folklore Society proposed that it should be marked, there was local support. With limited funding and volunteer labour, Baker spearheaded the undertaking.

Most of the physical work was done in 1960 or ’61. Some 260 plaques, set on slender concrete posts standing five feet above ground and buried three feet deep, designate the 310-kilometre trail; they are discernable from over a kilometre away. It wasn’t just a straight line from A to B, and as Baker said, “We hope people 800 to 1000 years from now will say, ‘here was the southernmost thoroughfare of the early trails across the Western Canadian plain.’ You can see the way they skirted hills and sloughs and chose the most gradual slopes for the toiling oxen and ponies.”

William Everett Baker was not born in in the province of Saskatchewan, nor was he a Canadian citizen. But you could say, ‘he left his marks on the Canadian prairie.’ He died in 1981 and is buried in his beloved prairie soil at Swift Current.

NWMP Trail Markers Accessible to the Public

Wood Mountain Provincial Historic Park

Wood Mountain Regional Park

Chimney Coulee Historic Site

Eastend, near the T-Rex Interpretive Centre

Fort Walsh National Historic Site